Larry Summers has an interesting tweet stream (HT Marginal Revolution) on the state of monetary policy. Much I agree with and find insightful:

Can central banking as we know it be the primary tool of macroeconomic stabilization in the industrial world over the next decade?...There is little room for interest rate cuts..QE and forward guidance have been tried on a substantial scale....It is hard to believe that changing adverbs here and there or altering the timing of press conferences or the mode of presenting projections is consequential...interest rates stuck at zero with no real prospect of escape - is now the confident market expectation in Europe & Japan, with essentially zero or negative yields over a generation....The one thing that was taught as axiomatic to economics students around the world was that monetary authorities could over the long term create as much inflation as they wanted through monetary policy. This proposition is now very much in doubt.Agreed so far, and well put. "Monetary policy" here means buying government bonds and issuing reserves in return, or lowering short-term interest rates. I am still intrigued by the possibility that a commitment to permanently higher rates might raise inflation, but that's quite speculative.

and later

Limited nominal GDP growth in the face of very low interest rates has been interpreted as evidence simply that the neutral rate has fallen substantially....We believe it is at least equally plausible that the impact of interest rates on aggregate demand has declined sharply, and that the marginal impact falls off as rates fall. It is even plausible that in some cases interest rate cuts may reduce aggregate demand: because of target saving behavior, reversal rate effects on fin. intermediaries, option effects on irreversible investment, and the arithmetic effect of lower rates on gov’t deficitsCentral banks are a lot less powerful than everyone seems to think, and potentially for deep reasons. File this as speculative but very interesting. Larry has many thoughts on why lowering interest rates may be ineffective or unwise.

The question is just how bad this is? The economy is growing, unemployment is at an all time low, inflation is nonexistent, the dollar is strong. Larry and I grew up in the 1970s, and monetary affairs can be a lot worse.

Yes, the worry is how much the Fed can "stimulate" in the next recession. But it is not obvious to me that recessions come from somewhere else and are much mitigated by lowering short term rates as "stimulus." Many postwar recessions were induced by the Fed, and the Great Depression was made much worse by the Fed. Perhaps it is enough for the Fed simply not to screw up -- do its supervisory job of enforcing capital standards in booms (please, at last!) do its lender of last resort job in financial crises, and don't make matters worse.

But how bad is it now? Here Larry and I part company. Larry is, surprisingly to me, still pushing "secular stagnation"

Call it the black hole problem, secular stagnation, or Japanification, this set of issues should be what central banks are worrying about...We have come to agree w/ the point long stressed by Post Keynesian economists & recently emphasized by Palley that the role of specific frictions in economic fluctuations should be de-emphasized relative to a more fundamental lack of aggregate demand.

The right issue for macroeconomists to be focused on is assuring adequate aggregate demand.My jaw drops.

The unemployment rate is 3.9%, lower than it has ever been in a half century. It fell faster after about 2014 than in the last two recessions.

Labor force participation is trending back up.

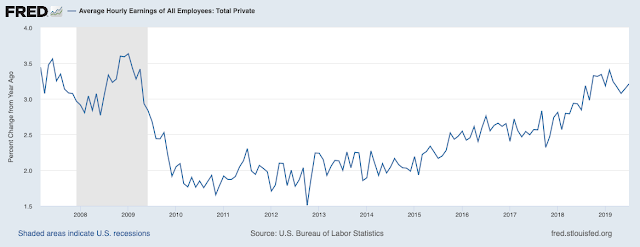

Wages are rising faster and faster, especially for less skilled and education educated workers.

There are 8 million job openings in the US.

Why in the world are we talking about "lack of demand?

Larry had a point about secular stagnation in about 2014. The Great Recession was dragging on seemingly forever. There was a good debate about "secular stagnation" vs. sand in the gears -- the cumulative effects of Obamacare, Dodd Frank, and the regulatory war on capital. But those days are over. How can anyone be seriously talking about "lack of demand" now?

Yes, despite the clearly full employment labor market, GDP is growing more slowly than I think is possible, and I can infer Larry agrees. But at full employment slow GDP growth comes from too slow productivity growth.

Let me suggest the alternative:

The right issue for macroeconomists to be focused on is assuring adequate aggregate supply.[This is me, not Larry]. When you're out of recession and financial crisis, further growth comes from "supply." And there is plenty to work on there. Alas, supply requires a Marie Kondoing of our public life, not a grand new initiative. Fix all they little things, zoning, agricultural policy, tax reform, reducing disincentives of social programs, continued regulatory reform, cutting tariffs, occupational licensing, and on and on. Macroeconomists (and growth economists) should be focusing on microeconomics.

Larry goes utterly in the opposite direction:

Obviously fiscal policy needs to be a major focus, especially given what low or negative interest rates mean for the sustainability of deficits.

But the level of demand is also influenced by structural policies: e.g. pay-as-you-go social security, higher retirement ages, improved social insurance, support for private infrastructure investment, redistribution from the high-saving rich to the liquidity-constrained poor.OMG. In case you can't read between the lines, the first paragraph means deliberate even larger deficits. "infrastructure investment" in the US today means more $4 billion per mile subways and high speed trains to nowhere. Redistribution to the liquidity constrained means forcibly taking away hard earned money to give it to people who have maxed out their credit cards.

(The latter is an especially pernicious argument. If the point is to give money to those who will consume it more effectively than us hopelessly frugal savers, then give it to the liquidity constrained rich too, and do not give it to the frugal poor. This is a classic case of an answer in search of a question, as the question does not lead to income-based redistribution.)

Larry isn't quite at the Magical Monetary Theory and Green New Deal blowout here. But I only infer that from his previous statements critical of those for going too far. This is darn close and all in the same direction.

One might defend Larry that previously he was talking about contingency plans for stimulus in a recession. But these are permanent, structural policies that come and stay for a generation.

I thought of Larry as the epitome of centrist, sensible, technocratic Democratic Party stalwarts, alongside say Alan Blinder, who wrote quite sensibly in the WSJ warning against the excesses of Green New Deal and health care for all. I still have hope that that sensible wing of the party will prevail, and join with the sensible wing of Republicans (there still is one) to fix the supply end of our country. But this is an amazing sharp left turn.

Larry's closers with another intriguing thought.

The high inflation and high interest rates of the 1970s generated a revolution in macroeconomic thinking, policy and institutions. The low inflation, low interest rates and stagnation of the last decade has been longer and more serious and deserves at least an equal responseWell put and yes indeed. But in my view, Alvin Hansen's 1939 speculations about eternal lack of demand and a soft version of AOC-Sanders-Warren deficit financed spending blowout and "redistribution" aren't it. Marie-Kondoing the massive clutter and disincentives on the growth side of our economy is.

from The Grumpy Economist https://ift.tt/2ZpcG6n

0 comments:

Post a Comment