I have been emphasizing the Fed's dilemma: If it raises interest rates, that raises the U.S. debt-service costs. 100% debt to GDP means that 5% interest rates translate to 5% of GDP extra deficit, $1 trillion for every year of high interest rates. If the government does not tighten by that amount, either immediately or credibly in the future, then the higher interest rates must ultimately raise, rather than lower, inflation.

Jesper Rangvid points out that the problem is worse for the ECB. Recall there was a euro crisis in which Italy appeared that it might not be able to roll over its debt and default. Mario Draghi pledged to do "whatever it takes" including buying Italian debt to stop it and did so. But Italian debt is now 160% of GDP, and the ECB is still buying Italian bonds. What happens if the ECB raises interest rates to try to slow down inflation? Well, Italian debt service skyrockets. 5% interest rates mean 8% of GDP to debt service.

Central banks first stop bond buying and then raise interest rates. Whether U.S. bond buying programs actually lower treasury yields is debatable. But there is no question that the ECB's bond buying keeps down Italy's interest rate, by keeping down the risk/default premium in that rate. If the ECB stops buying, or removes the commitment to "whatever it takes" purchases, debt service costs will rise again precipitating the doom loop.

Jasper:

The ECB is caught in a dilemma.

The ECB knows that very expansionary monetary policy, combined with already high inflation and strong economic growth, creates a serious risk that inflation and inflation expectations run wild.

The ECB also knows, however, that if it tightens monetary policy, i.e. stop asset purchases and raise rates, debt-burdened Eurozone countries will face severe challenges.

Take Italy as an example. At the end of last year, Italian public debt corresponded to 160% of Italian GDP. This is a lot of debt. ...

Low interest rates have been kind

, in spite of a 50% higher debt burden, debt-servicing costs for Italy has been cut by a third from 2007 to 2020. The reason is of course low interest rates.

...In addition to the global fall in rates, though, the ECB has been buying Eurozone government debt in massive amounts, significantly reducing rates even further. ...

|

| Figure 11. ECB holdings of Italian debt securities. Millions of euros. Source: Datastream via Refinitiv. |

The ECB has bought a lot of debt. First, in relation to the Public Sector Purchase Program (PSPP), launched after the Eurozone debt crisis, and, second, in relation to the Pandemic Emergency Purchases Program (PEPP), the program launched to battle the corona crisis. Under the PSPP, ECB amassed Italian debt worth EUR 400bn. Under the PEPP, it amassed EUR 300bn. In total, the ECB holds Italian debt worth EUR 700bn, see Figure 11. The ECB owns close to 25% of all outstanding Italian public debt....

|

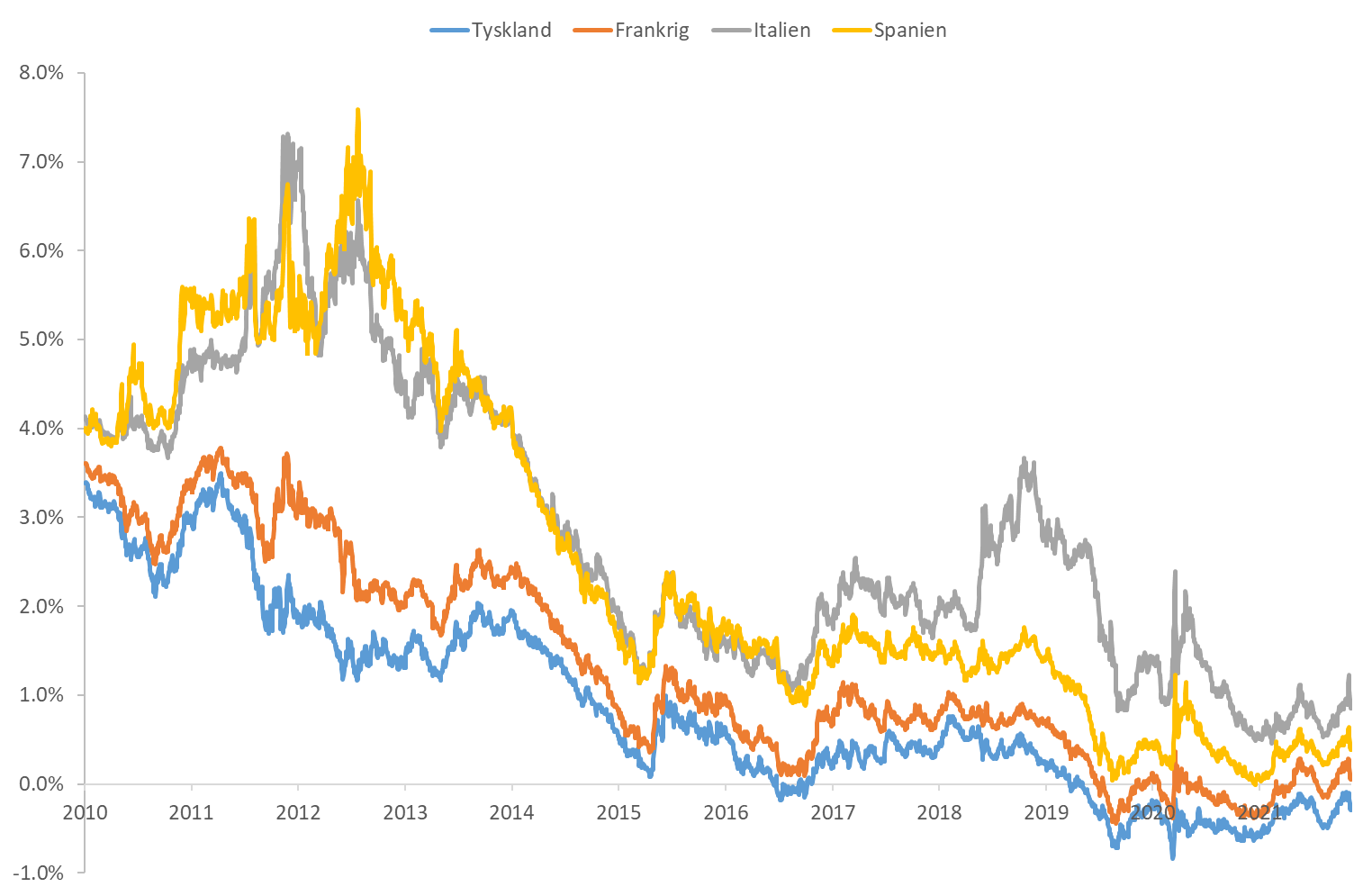

| Figure 12. Yields on long-dated Eurozone government bonds. Source: Datastream via Refinitiv |

Many of us remember the Eurozone crisis in 2010-2013. Italian yields reached more than seven percent in 2012, see Figure 12. Yields only came down after Mario Draghi’s famous “we will do whatever it takes” speech in 2012 (link). ECB saved Italy, thereby saving the Eurozone.

This is an important reminder that it can happen. For the U.S. a large default/inflation premium to real interest rates is a theoretical possibility, and perhaps a memory of the early 1980s if one interprets that episode as a fear of return to inflation, or otherwise a memory of the 1790s. For Europe this happened, and only 10 years ago.

Jasper does not mention the interesting question, what happens to all these bonds on the ECB balance sheet, or the bonds it will surely acquire if Italian spreads widen again, in the event of default.

Jasper also does not mention one small piece of good news. I gather Italian debt is somewhat longer-term than U.S. debt, though I don't have a good number handy. That fact means that higher real interest rates (including default premium) only spread into interest costs slowly.

In sum,

the ECB is stuck in a corner. Whether one fears this round of inflation will persist or not, the fact that the ECB is constrained by fiscal considerations is problematic. If the ECB one day needs to raise rates, it will face the dilemma described above.

What to do?

What is the solution? This will take us too far in this blog, but it lies in the old discussion of macroeconomic reforms in certain European member states, directing fiscal policy to a healthy path, improving productivity and competitiveness, and in the end generate higher growth. This is easier said than done.

Draghi was quite clear, that "do whatever it takes" was a temporary expedient, to give Italy room for structural and fiscal reforms. Those (predictably?) did not happen so here we are again. Is it too late? Italy will surely not reform before a crisis looms, so the case has to be that a crisis is severe enough to finally provoke growth-oriented economics.

The ECB, however, remains stuck between a rock and a hard place. As the Fed will be if it tries to substantially raise interest rates.

from The Grumpy Economist https://ift.tt/3IJ7G4f

0 comments:

Post a Comment