America has essentially given up on containing the corona virus, and will just let it spread while we await a vaccine. Oh sure, our governors and other public officials flap around about wearing masks and social distancing. But there is no serious public health effort. (If you're in California, I encourage you to listen to NPR's faithful coverage of our Governor Gavin Newsom's noon daily press conference. Never has anyone so artfully said so little in so many words.)

A vaccine is a technological device that, combined with an effective policy and public-health bureaucracy for its distribution, allows us to stop the spread of a virus. But we have such a thing already. Tests are a technological device that, combined with an effective policy and public-health bureaucracy for its distribution, allows us to stop the spread of a virus.

For that public health purpose, tests do not need to be accurate. They need to be cheap, available, and fast. When the history of this virus is written, I suspect that the immense fubar, snafu, complete incompetence of the FDA, CDC, and health authorities in general at understanding and using available tests to stop the virus will be a central theme. (Well, forecasting historians is a dangerous game. Already "the virus increases inequality and social injustice" seems to be the narrative of the day.)

Marginal revolution has three insightful posts on the issue. "Bill Gates is angry" starts with a comment on the fact that currently, once you get a test, it can take days or even weeks to get the results.

..that’s just stupidity. The majority of all US tests are completely garbage, wasted.

If the point of the test is to find out who has it, and isolate them, then an answer that comes back after they've gone out to spread the virus to friends, family and co-workers is completely wasted. Gates has an econ-101 insight into why this is happening:

If you don’t care how late the date is and you reimburse at the same level, of course they’re going to take every customer...You have to have the reimbursement system pay a little bit extra for 24 hours, pay the normal fee for 48 hours, and pay nothing [if it isn’t done by then]. And they will fix it overnight.

I know a great such reimbursement system, but I'll hold that in suspense. (You can probably guess what it is.)

A second great insight:

"Stack push-pop testing" or LIFO (last in, first out). Currently labs work on a first come first served model. New samples are pushed to the back of the line. Well, that's only fair, you say. But when the lab is backed up a week, it means that none of the tests are useful. Instead, labs should simply throw out any samples that are more than, say, two days old, and do the most recent samples first.

just as many tests will be completed as under the current model but the tests results will all come back faster and be much more useful. ... faster, more useful tests will help to end the crisis by reducing the number of infections.

My emphasis. This is of course what labs would do if they faced the economic incentive suggested by Mr. Gates.

The central problem, I think, is conceptual. What are tests for? Well, there are two answers. A test can be useful to help doctors to evaluate an individual patient, and decide what treatment is appropriate. Or a test can be useful to public health authorities, to businesses, to people, to sports teams, to airlines, to bars and restaurants to find and isolate people likely to be sick, and to clear people not likely to be sick for public interaction. The requirements for speed, cost, and accuracy those two purposes are radically different. Exhibit A is group testing. Group testing is not a good solution when there is one patient in an emergency room. Frequent repeated group testing is ideal if there are 100 employees, school children, airline passengers, etc. that you want some probabilistic assurance are not likely to have the virus.

This conceptual hurdle, I think, lies behind the FDA blocking saliva tests, for example. MR makes this and other key points in Rapid tests.

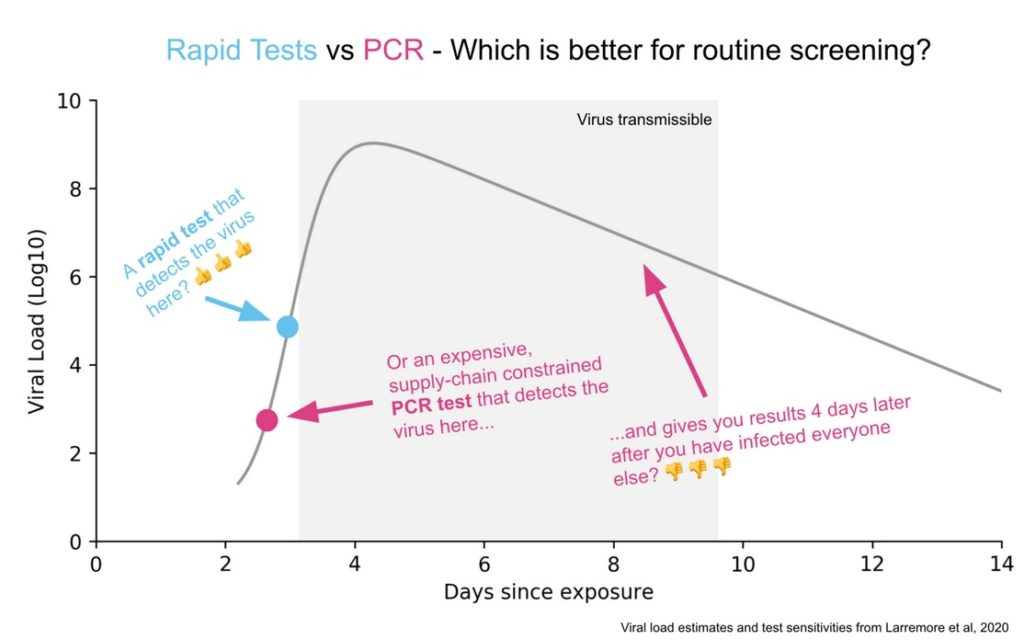

A test that isn't very good at picking up people with small viral loads, but gets answers back quickly is better than a test that is more sensitive and gets answers back in a week. The same point goes for a test that is cheap and lots of people will take, one that you can get without an expensive doctor referral and prescription, and a test that is half as accurate but twice as many people take it -- for the purpose of public health. Again, the purpose of stopping contagion is different from the purpose of diagnosing and treating a given sick patient. The FDA seems only to understand the latter, not the former. When did "how fast can you get test results back?" enter its calculus for certification?

Alex Tabarrok on MR:

I do think we are beginning to see some recognition of the difference between infected versus infectious and the importance of testing for the latter. What is frustrating is how long it has taken to get this point across. Paul Romer made all the key points in March! (Tyler and myself have also been pushing this view for a long time).

In particular, back in March Paul showed that frequent was much more important than sensitive and he was calling for millions of tests a day. At the time, he was discounted for supposedly not focusing enough on false negatives, even though he showed that false negatives don’t matter very much for infection control. People also claimed that millions of tests a day was impossible (Reagents!, Swabs!, Bottlenecks!) and they weren’t impressed when Paul responded ‘throw some soft drink money at the problem and the market will solve it!’. Paul, however, has turned out be correct. We don’t have these tests yet but it is now clear that there is no technological or economic barrier to millions of tests a day.

Go yell at your member of Congress.

Again my emphasis for a nice epigram. I like Alex's optimism. Your member of Congress has left town, unable to agree whether to only shower the electorate with $5 trillion of newly printed money, or $7 trillion, and how much pork to larder in with that.

What's a better reimbursement model? That tests for covid-19 are shoved through America's uniquely dysfunctional health insurance system is ridiculous. How about a free market? People, organizations, and businesses should be able to buy freely, without prescription, any test that anyone wants to sell them. Will some tests be less than perfect? Yes, but there are lots of ways of getting information about which tests work. Why is a covid-19 test more regulated than a pregnancy test? Why is one an expensive and time-consuming prescription, insurance, referral product and the other not? I guarantee you lots of tests, much faster results, and a quick end to the virus. Sure, "can't afford..." So let the market operate on top of the insurance system.

Of course as for paying, there is a good case that the government pay for any tests anyone wants. National weekly testing would be a lot cheaper than $5 trillion. Again the purpose is public health, a classic public good. But the price signal that we only buy your tests if we like the results, the accessibility, the customer service, the speed, are important. Allowing a cash option on top of the usual bureaucratic snafu would solve the problem quickly. Yes, some people can't afford. But there are lots who can, and they spread the disease just as much as those who can't!

In the meantime, we're back to the Middle Ages. I note governors imposing quarantines. All travelers from "high infection" areas must self-quarantine for two weeks. Unlike in the Middle Ages, nobody is enforcing this sort of ban, so all it does is to force law abiding businesses to close, and further kill airlines and hotels. (Colleges that could handle on-campus restarts, for example, are going online because they can't let students travel to get there.) Ah, dear governors, have you heard about tests? How about when you step on a plane we all spit in a bucket, and a group saliva test clears everyone -- or not, in which case each individual gets a test.

So we wait for the vaccine. But vaccines also -- maybe even more than tests -- require a competent public health bureaucracy if they are to be used to stop a pandemic. Who will pay? Which vaccines get to be sold? How hard is it to get one? Who gets it and when? The vaccine does not just protect you, it protects all the people you want to infect. Properly using a vaccine to stop an epidemic is not an immensely simpler bureaucratic and public health challenge than properly using tests to stop an epidemic. Will our public health bureaucracies do much better next time around?

from The Grumpy Economist https://ift.tt/3iuOeKS

0 comments:

Post a Comment